4+2Section 1.2 Introduction to the interface of RStudio and R language

Now I assume that R and RStudio are correctly installed on your computer. You can start by opening RStudio. You will see a lot of things on your screen, many blocks, many menus, and it can be quite overwhelming. No worries! This is exactly what this section is about!

1 The interface of RStudio

1.1 General overview of the interface: Blocks, blocks, blocks and blocks

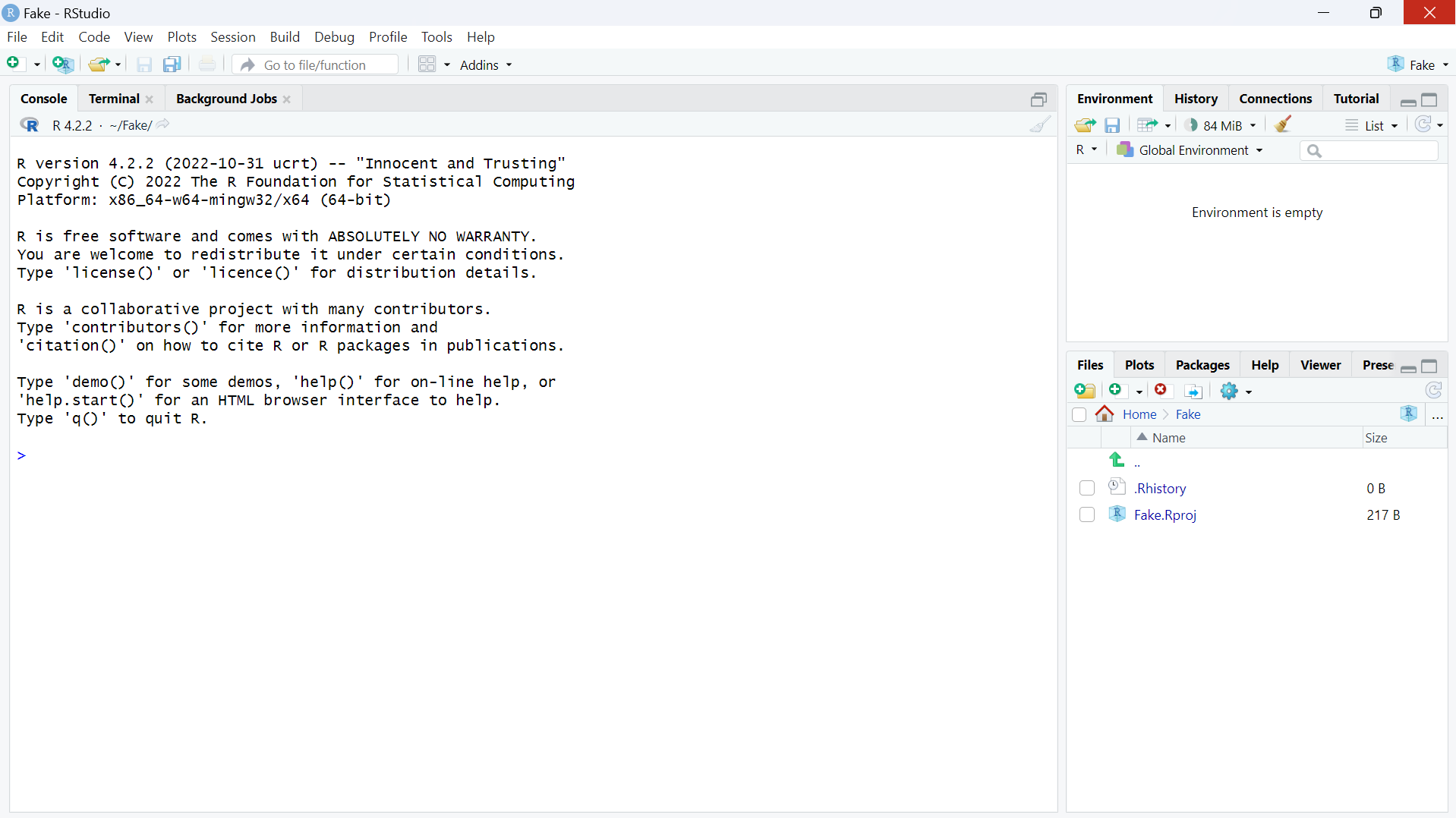

You may see the following picture on your screen after opening RStudio:

The best way to apprehend RStudio is to understand the interface as blocks, which are here for different purposes.

When you open RStudio for the very first time, you should get something similar as in the image above, with three blocks in the same order. But it’s also possible that you have something else. If that’s the case, this is completely normal and this won’t affect anything for the following steps!

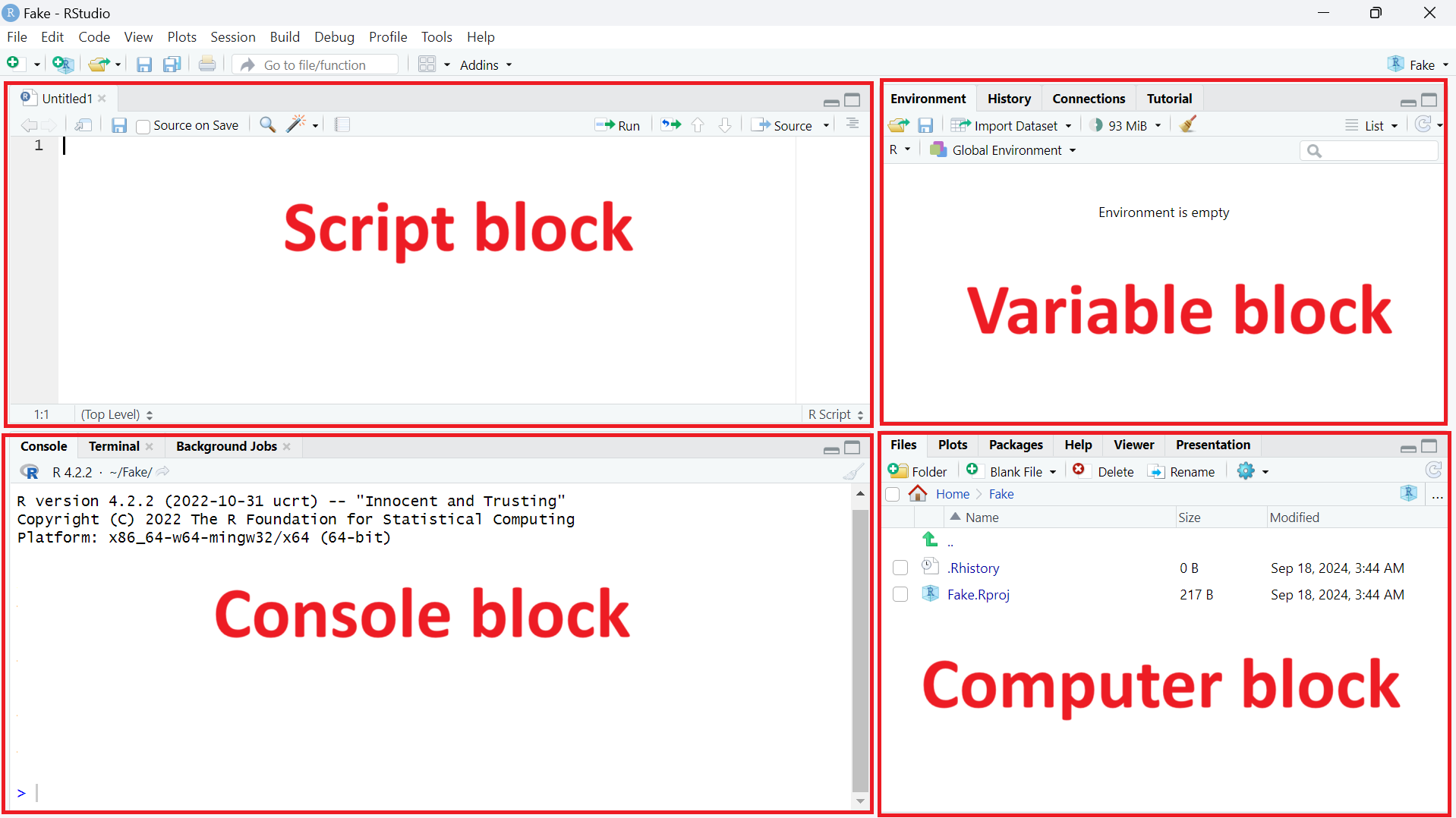

There are four main blocks, as in the following image. I give them unofficial names so that it will be easier to refer to them. There is one block that I call the ‘computer block’, a second one the ‘data block’, a third one the ‘script block’, and finally the last one, the ‘console block’.

You may not be able to see the ‘script block’ on your computer for the moment, and again, this is completely normal! Just follow the steps below.

1.2 The computer block

The ‘computer block’ is the one on the bottom right side. I call it the ‘computer block’ but it’s actually much more than that, but let’s keep it simple for the moment. First, click on the Files button. You will see that there is a list of files and folders from your computer. This is actually the interface you can use to communicate and navigate directly with your computer!

Again, look at all the options and play with them to understand what everything’s about:

Click on the files. How do these open? In RStudio? Directly on your computer?

Try to go to other folders on your computer using the computer block. You’ll see there is no mystery, this is just like navigating on your own computer as you usually do!

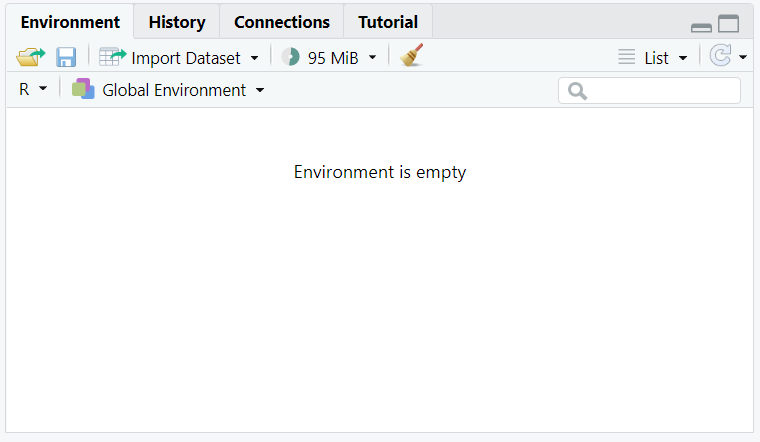

1.3 The variable block

The ‘variable block’ is the one on the top right side, as in the image below.

Basically, the most important tab is the ‘environment’ one. This is where the variables we create when coding will be stocked. The term ‘variable’ can be quite abstract at the moment, so let’s just exemplify it with our first code. R can be used as a simple calculator. In the ‘console block’, just write the following code, end press ‘enter’:

Normally, you’ll see this:

4+2[1] 6And indeed, ‘4 + 2’ equals 6. Now, let’s play a game. You want to obtain the number 8, but you have to use ‘4 + 2’. One option is to add 2 one more time, and you will write the following code:

4+2+2[1] 8The game may continue, and you will need to write even more. This is when the variables can be useful. Try the following code:

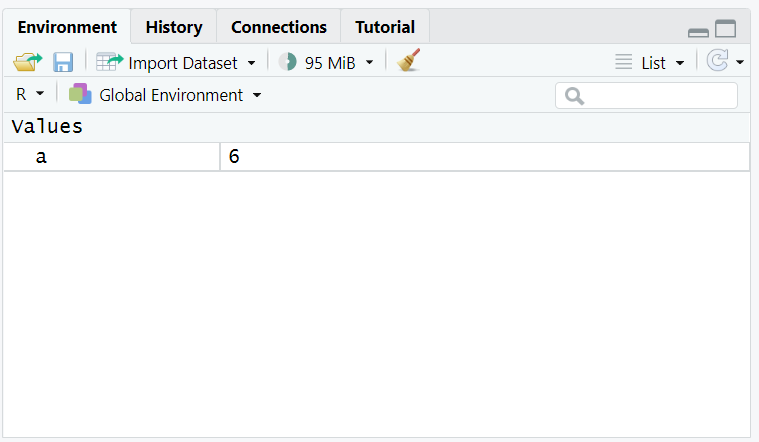

a <- 4+2Unlike what you have seen before, nothing appears in the console anymore. But there is something new in the variable block:

You stocked the calculation ‘4+2’ as a variable, and you can call it anytime you want! For example, you can call it by simply writing a in the console, and you can also add 2 to it by writing a + 2, and you’ll see something as follows:

> a

[1] 6

> a+2

[1] 8This example is just here to show what the ‘variables’ are. With just simple calculations like the ones above, it seems to be quite useless. But you’ll realize very quickly through this tutorial that variables are not only useful, but also necessary to handle more data.

1.4 The console block

Now let’s talk very briefly about the ‘console block’. You just had a glimpse of it when reading the section on the variable block. Actually, there’s not a lot more to say about it. The console block is the place where the code is written and being run.

In addition to the ‘Console’ tab, there are also the ‘Terminal’ tab and the ‘Background Jobs’ tab. Despite their importance, we won’t have have to use them in this tutorial. So let’s just skip them!

1.5 The script block

The ‘script’ block is where you’ll work most of the time. You can see it as the Word or the Note Pad of RStudio. You will better understand the importance of the scripts, one more time, with an example. If you’ve followed Section 1.3, you can see that you have the same code as below in your console.

> 4+2

[1] 6

> a <- 4+2

> a

[1] 6

> a+2

[1] 8Now, just close R and reopen it. All the codes disappeared! We usually use R for much more than a simple calculator, and we always end up with hundreds of lines of codes. Imagine if you need to rewrite everything each time you close and reopen R… and this is where the scripts are useful!

Let’s do a simple exercise with the script. First, open a new script by clicking on “New File”, and then the first option, called “R Script”.

Write the lines below in the script block:

4+2

a <- 4+2

a

a+2After that, select everything, and click on ‘Run’. You can also have a look at the short video below.

This is how you run a script! Alternatively, you can select everything (or just the line you interested in), and press ‘enter’ on your keyboard. Now you can save your script (“File > Save”) and close R. Find the file you just saved on your computer and open it. Your code is still here!

1.6 Exercise: Play with your blocks!

Your four blocks are like construction toys you can play with. You can make them disappear and then reappear, you can change their size as you wish, and you can even change the background color. In other words, make RStudio your own!

This is how you can change the size of the blocks with your mouse:

This is how you change the background color of RStudio:

Path: Tools > Global Options... > Appearance > Choose the theme you like in 'Editor theme'

I personally change the sizes of the blocks dynamically, depending on the task I’m doing. For example, if I’m writing more complex lines of codes which could be confusing, I enlarge the script block to be sure I’m not missing any parenthesis or comma. When I’m drawing plots, I make the computer block bigger to visualize more clearly what I’m doing, and it helps me to know if I want to add or change anything on the plot.

Everyone’s experience is different, it just depends on what your preferences are. So, really, make it your own!

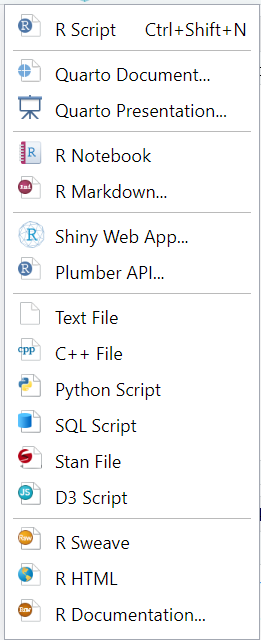

1.7 Bonus: More about the script block

As you opened a new script, you may have realized that you had the choice between many options, as below.

We only used the “R Script” type, but you can actually do much more depending on what you want to do in your project. For example, you have “Quarto Document” or “R Markdown” which are like “R Script”. The difference is that R Scripts only save your codes, while Quarto Documents or R Markdowns allows more options, and especially to render out in a PDF or markdown file. By doing so, we can share our code along with the output of the code in a beautiful way, which is very important for Open Science!

You’ll also remark that even if we are using R, it is actually possible to write with other programming languages, such as HTML or Python. While this is not the case for R Scripts, it is possible with other types of scripts. You can even design a whole website using R, and ask R to transfer your data online… This is indeed how I am designing the website of the tutorial!

Script files have many very useful options, so many that I decided to dedicate a whole section to it. Jump here (link provided later) if you want to know more!

2 Libraries

2.1 What is the concept of the “libraries”?

You can do many things with R. Among others:

- Basic calculations

- Data manipulation

- Draw figures or plots of your data

- Create geographical maps

- Run simple and advanced statistics (summaries, t-tests, ANOVA, LMR, GLMR, Bayesian statistics, etc.)

- Design a whole website

- Preprocess neuroimaging data (EEG, fMRI, etc.)

- Download data from the web to be further manipulated

- Create applications

And many many other possibilities. You may have a sense of it, the more complex the task is, the more codes it requires. For example, it is not the same to calculate ‘2+4’ and putting statistical data on the map of Europe!

It can be overwhelming, and we can even have the feeling that quantitative research is not for us after all. Good news! We actually don’t need to write all the codes from scratch!

R is free and open source, it is a collaborative concept. And this is very important to be aware of this: Nobody, nobody, writes all the raw codes for each task in one script. Just like we read articles and books instead of doing all the research on the field when we want to know more about something, we can rely on other people’s work when writing codes.

People wrote, and more importantly, published, articles and books so that we can have access to more knowledge.

People wrote, and more importantly, shared online, lines and lines of codes and functions such that we can have access to them, use them, instead of rewriting everything.

We need to introduce some concepts now:

- Lines of codes

- Functions

- Packages/Libraries

| Name | Concept |

|---|---|

| Line of codes | Just the code you write in the script/console to perform something specific. They are usually the most simple. |

| Function | Sometimes, you need more than one line of code to perform a task. You may even want to perform the exact same task several times, but with different data. Of course, you can just copy and paste the same code everytime, but you can also choose to simplify it into one line of code. This is what a function is: a cluster of lines of codes |

| Library/Package | And very often, you’ll need to perform many tasks which require more than one function. You can choose to write all the functions by hand anytime you need them. Or you can just have them already loaded somewhere in R, such that you can refer to them later when you need them. This is what a library or package is: a cluster of functions |

There are many many packages available for free with R. You can find them here. And they are even more that are not directly available from the R website, but developped and distributed by other people (generally on Github). They always come with a logo, as below.

We will very often refer to some of them, such as “readxl” to import data from Excel, “ggplot2” to draw figures, “tidyr” and “dplyr” to manipulate data, etc.

2.2 How to install and use libraries?

Installing libraries is quite easy. You have two ways to do so:

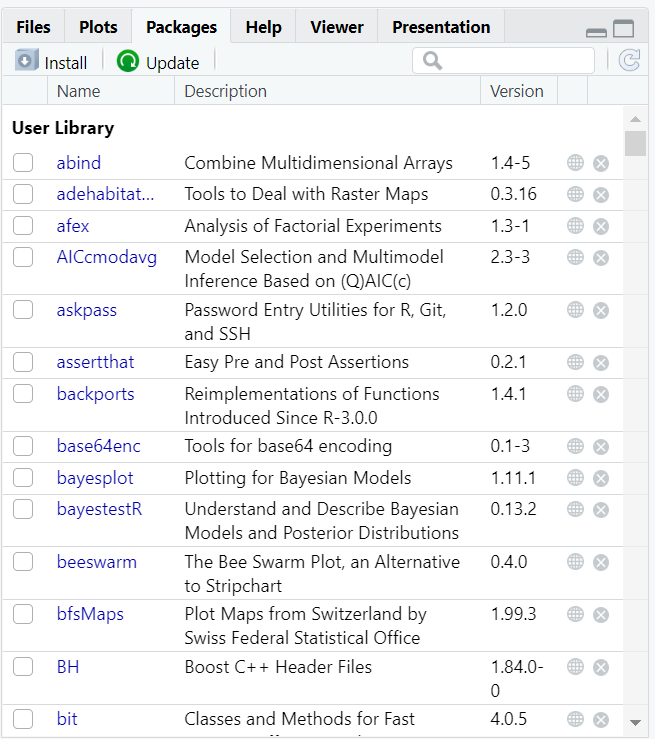

Using the Computer block

So far, we’ve only mentioned the Computer block as the block where you can browse the folders and open the files on your computer. This block actually has more functions. If you look at the tabs, you will remark that we’ve only talked about the “Files”.

Now we will turn to the “Packages” tab, as in the image below. What you need to do is to click on “Install”, you write and select the name of the library you want to install, and finally click on “Install”. That’s it!

Give R a couple of minutes while it’s downloading the data and installing on your computer.

Using the Console block

Alternatively, you can download/install packages directly from the Console block. You just need to write one line of code:

install.packages("[Name of the package you wish to install]")For instance, if you want to install the package ‘ggplot2’, which is used to draw figures, here is what you need to write:

install.packages("ggplot2")You will remark that for installing the packages, you need to write the name of the package between quotation marks

Now that you have downloaded the packages you need, this does not mean that you can use the functions in the libraries right away. The packages are installed, but you need to “call” them, or to load them, such that they are ready to use. Note that no quotation marks are used with this function.

library([Name of the package])

library(ggplot2)Let’s keep the metaphor of the articles and books published by other people. You want to prepare a memorable dinner, and to do so you need to buy a book with recipies that you can’t find online. To do so, you go to the bookstore and buy this wonderful book. Back home, you just put it on your bookshelf. The step of buying the book and bringing it back home corresponds to the ‘install.packages()’ step.

Does having the book at home mean that you just need to go to your kitchen and start cooking? Of course not! You need to have this book opened with you in the kitchen to follow the recipies! This is exactly what we are doing when we load the packages in the ‘library()’ step!

3 Some basic elements of R language

This subsection will introduce some basic elements of R codes that cannot be avoided. I will introduce codes referred to as ‘R-based’, meaning that there is no need to install any additional packages.

While you’re going through the examples below, don’t hesitate to open an R script, copy and paste the codes, run them to see what happens. In addition, you can also modify the codes and try new things. You may run into errors, but that’s ok. From my experience, it is the best way to get used to the R interface.

3.1 First things first: The ‘working directory’

This is one of the most important step, and also something that I always (and everybody should) check before anything else. The ‘working directory’ refers to the folder in your computer R is looking into. While you can navigate in the folders of your computer using the Computer block, this does not mean that R remembers where you are. To do so, you have to tell R:

This is THE folder where the files I will load are, THE folder where my script will be saved, THE folder where all my files will be saved

This is what the ‘working directory’, it is THE folder. Now, how to set your working directory, THE folder?

Use the Computer block to navigate in your computer until you are in the folder you wish to work in,

Click on the small image of the wheel, and then click on “Save as Working Directory”

And you are done! You will see that a line of code appeared in the Console block, actually setting the working directory.

3.2 Your first script: Some syntax and vocabulary of R

3.2.1 Add comments

A useful tip when writing R code is the possibility to add comments. I use it all the time such that I can annotate why I used this function, the size I want to print my figure, etc. Comments are marked with the hashtag sign “#”. See the example below.

Note that you can add as many hashtag signs as you want. I personally have the habit to use three hashtag signs, but you could also just use one.

### This is a line of comment. I won't be run in the console, even if it is copied there.

2+4 ### We can also add comments after a code. In that case, it will only run the code at the beginning of the line, and ignore everything after the # sign[1] 6Now that you know how to add comments in the script you have opened, just comment every line, even the ones that you created yourself!

3.2.2 Basic calculations

We have already referred to basic calculations in the previous subsections. These so-called basic calculations can even be complex, as below.

2 + 343 * 34 / (5 - 342 + 45 * 36)[1] 11.089633.2.3 Assigning variables

We have also already mentioned how to assign variables in previous subsections. Let’s recall it below.

a <- 4+2Another way to assign variables is by using the equal sign “=”. You just obtain the same results. I prefer using “<-” because I find it visually more salient, but it depends on one’s preference.

a = 4+2You can also assign strings of letters. For example, you can try to add “This is my first script” to the variable “b”.

b <- This is my first scriptYou will remark that… it didn’t work! You surely had the following message:

Error: unexpected symbol in "b <- This is"This is “This is my first script” has never been defined in R. In other words, R does not know what you are talking about! If you want to add strings of words, you need to use the quotation marks, as below.

b <- "This is my first script"You can also assign tables, datasets, plots, etc. You can even assign variables to variables. Try this below:

b <- aWhat happened here? You had a variable called ‘a’, which had the value “6”. You also had the variable called ‘b’, which had the value “This is my first script”. In the above line of code, you are asking R to assign the value of the variable a to b… in other words, the value of ‘b’ becomes the same as ‘a’!

3.2.4 Load data from your computer to R

You may have already collected data, and you want to import your dataset into R. For this section, let’s use the data from the survey of “Great American Coffee Taste Test”. You can download the file here. (source of the data: https://mavenanalytics.io/data-playground

Don’t forget to place this file in the folder you are working in, and to set this folder as your working directory!

Now you have two ways to import the data into R:

with a line of code, or

with the R interface.

Let’s first do it with the code below.

data <- read.csv("~/fake/GACTT_RESULTS_ANONYMIZED_v2.csv", header=TRUE)Now let’s decompose this:

read.csv(). This is the function which is used to import the file, which is a CSV file.

There are two elements inside the function, which are seperated with a comma:

“~/Fake/GACTT_RESULTS_ANONYMIZED_v2.csv”. This is the path to access to the file, as well as the full name of the file

header=TRUE. This means the first line of the table corresponds to the titles of the columns (you can try and change to “header = FALSE” to see what happens!).

Finally, the dataset is assigned to the variable called “data”.

Why do we need to assign the data to a variable? As I always say, computers are very powerful and very stupid at the same time: they are here to do in a very short amount of time exactly what you tell them to do. In other words, if you only use the “read.csv()” function, it will only read the data, and forget it, that’s it!

But what we want to do actually is to read the data and save them into R, such that we can do further manipulations. This is why we need to “save” them using variables!

The second way is to use the R interface. To do so, check you Variable block. You have a tab called “Import Dataset”. Just click on it, and then “From Text (base)…”. A new window will open, and you just have to choose the file you want to import.

Now you have a new window where you are asked to set the options to import the file:

You can change the name of the variable it will be assigned to. By default, it is the name of the file. Try to change to “data”.

You can also set the option that the first line corresponds to the names or labels of the columns. Where you see “Heading”, click on “Yes”.

And finally, you can click on “Import”.

And you are done, now you have a whole dataset ready for manipulation in R!

3.2.5 Data description and summary

I assume here that the dataset we just imported is still present in your environment. Now we will learn quick ways to describe and summarize the data we have.

The first step is to understand the structure of the dataset. This can be easily done with the ‘str()’ function.

str(data)You will obtain the following results. For clarity, I only give the first four lines here.

'data.frame': 4042 obs. of 111 variables:

$ Submission.ID : chr "gMR29l" "BkPN0e" "W5G8jj" "4xWgGr" ...

$ What.is.your.age. : chr "18-24 years old" "25-34 years old" "25-34 years old" "35-44 years old" ...

$ How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. : chr "" "" "" "" ...

$ Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee. : chr "" "" "" "" ...This is how to read the data:

- The first line indicates the nature of the dataset. This is a “data frame”, with 4042 rows and 111 columns. Afterwards, the str() function describes these 111 columns.

- The first column is called “Submission.ID”. The rows consist of strings of characters, and the str() function shows the data of the first four lines.

- The second column is labelled “What.is.your.age.”, and again it consists of rows of strings of characters.

- The same logic applies for all the lines.

You will remark that we are facing a problem. In this survey, the participants were asked their age, and then their results were annotated as “18-24 years old”, “25-34 years old”, etc. In other words, there are groups of age, but when the data were imported, R considered them as strings of characters. Now we need to tell R that there are groups. This is done with the “as.factor()” function.

data$What.is.your.age. <- as.factor(data$What.is.your.age.)Now let’s decompose this line:

- In the as.factor() function, we told R the date from which column needed to be transformed into groups. We now that this is the column called “What.is.your.age.” in the dataset called “data”. In R language, we write as follows: data$What.is.your.age.. The dollar sign is here to translate “inside of”

- If we just write this part, R will only transform this column as a group, but it will not save it. So we need to save this operation in a variable, and as we want to replace the column considered as strings of characters, we do not have to create a new variable: we just use this column!

Actually, the same problem occurs for the two following columns:

How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day., and

Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee.

So we need to do the same changes.

data$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. <- as.factor(data$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.)

data$Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee. <- as.factor(data$Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee.)And now let’s run the str() function again. Here are the results of the first four lines:

'data.frame': 4042 obs. of 111 variables:

$ Submission.ID : chr "gMR29l" "BkPN0e" "W5G8jj" "4xWgGr" ...

$ What.is.your.age. : Factor w/ 8 levels "","<18 years old",..: 4 5 5 6 5 8 4 1 5 1 ...

$ How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. : Factor w/ 7 levels "","1","2","3",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 1 ...

$ Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee. : Factor w/ 66 levels "","At a cafe",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 10 1 2 1 ...This is much more informative! For instance, this is telling us that there are 8 groups of age (in R, these are called “levels”). But maybe we would like to know the number of people per group among the 4042 participants. This can be done with the summary() function.

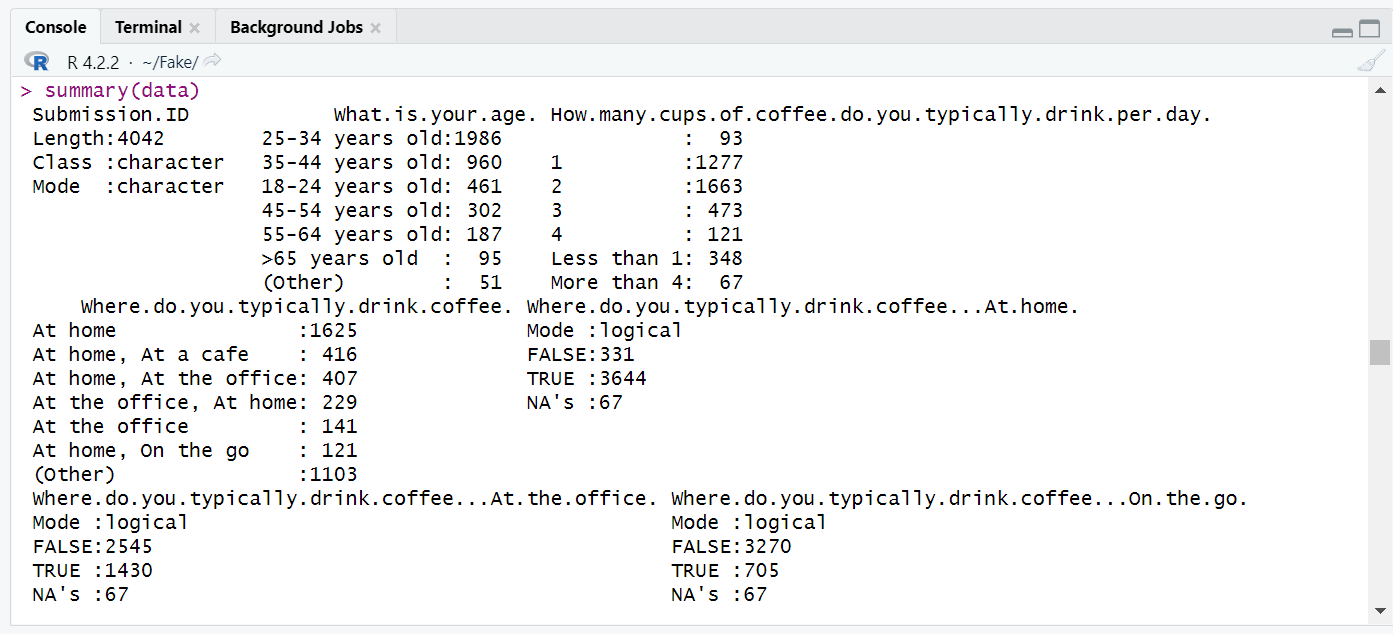

summary(data)This is what you obtain in the Console block:

How to read this? It is telling us that there are 1986 respondents in the “25-34 years old” group, 960 in the “35-44 years old” group, etc. Also that there are 1277 people drinking 1 cup of coffee per day, 1663 people 2 cups of coffee per day, etc.

3.2.6 Transforming the data: add, delete, change

Transforming the data is the task we spend the most of out time when doing the research. This can be tedious, but it is crucial to plot the right data and to conduct the right analyses. It is also very important to be aware of what we are doing when transforming the data. The aim is to make them more easily readable for R.

Data transformation or data manipulation does not mean new data creation or data selection!

We make changes to highlight some results, we select for ease of clarity, but such changes and selections are actually transformations and selection of the form, not the content!

You are actually already familiar with data transformation. In the previous section we have changed the class of the data of three columns: strings of characters to factors. I will exemplify here other changes we can make, but the list is not exhaustive at all.

You have surely remarked that there are many columns in the dataset we loaded. Generally, we collect more than we need, in case that in the end, we may need these data. But sometimes, having very large datasets can make us quite confused when trying to read and interpret the data. Therefore, sometimes, we would like a dataset with only the comumns we need.

For instance, we have talked of three columns so far in the previous section. We want to select them, in addition to the column indicating the ID of the respondents. We can do so with the code below.

data2 <- data[,c("Submission.ID",

"What.is.your.age.",

"How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.",

"Where.do.you.typically.drink.coffee.")]Again, let’s decompose this:

- The dataset from which we want to select data is called ‘data’. We select data from it by adding brackets, therefore “data[ ]”.

- The columns are selected by adding a comma first (there are reasons for this, but it is not important for our purpose now), and then adding the name of the column. For example, we may have written “data[,”Submission.ID”]“, and this selects the columns called ‘Submission.ID’.

- But we want to select more than one column. Unfortunately, we cannot write the names of all the columns directly. We need to inform R first that there is a list of columns. We use “c()” to do so.

- Finally, we save this into a variable. We may have saved this to “data” (i.e. “data <- data[….]”), but when doing so, we would have overwritten our original data. And if in the end, we realize that we need other columns, we have to redo everything! This is why it is good to have the habit to save into other variables when performing transformations of this kind.

Now we will learn another trick: How to check which groups we have. In other words, how many groups of age are there in the data we have? This can be done as below:

levels(data2$What.is.your.age.)[1] "" "<18 years old" ">65 years old" "18-24 years old"

[5] "25-34 years old" "35-44 years old" "45-54 years old" "55-64 years old"We use the level() function, and we inform R which columns we want to look at inside the parentheses. We obtain the results as above.

There are 8 groups, but the first one corresponds to people who did not reply. We would like to remove this in order to have a full dataset. If we do not want to do it with other libraries, we can do it as follows:

data2 <- subset(data2, What.is.your.age. != "")

data2$What.is.your.age. <- droplevels(data2$What.is.your.age.)- In the first line, we are telling R to remove the rows where the group is ““.

- To do so, we use the subset() function. In the parentheses, we set the parameters to tell R which rows to remove: dataset name (“data2”), column (“What.is.your.age.”), level (““).

- Note that we used the sign “!=”. This signs means “remove”. If we change this sign to “==”, it means “select”!

- We only removed the rows corresponding to ““, but not the label. This is the purpose of the second line.

Now you can run the “levels(data2$What.is.your.age.)” again. You will see that the level “” has indeed been removed!

levels(data2$What.is.your.age.)[1] "<18 years old" ">65 years old" "18-24 years old" "25-34 years old"

[5] "35-44 years old" "45-54 years old" "55-64 years old"If we look at the column called “How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.”, there is the same problem. We just have to run the same codes to solve this!

data2 <- subset(data2, How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. != "")

data2$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. <- droplevels(data2$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.)Now we would like to summarize the number of observations per group. And I will have to make an exception to what I said earlier: We are using the package called “dplyr”. So you will need to download it beforehand.

Here is the code you need to write:

library(dplyr)

data3 <- data2 %>%

group_by(What.is.your.age., How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.) %>%

summarize(Count = n())Let’s decompose this:

- In the first line, we just loaded the library we need.

- The sign “%>%” is here to say we are going to run the codes below it based on the dataset called “data2”

- The “group_by()” function is here to tell R which columns we will take into consideration. Notice that we do not need to write “data2$What.is.your.age.” since we used the “%>%” sign.

- Finally, the last line of code is the transformation we are performing: We want to summarize the data. Inside the “summarize()” function, we need to give the details of what we want to do (notice that you can also write “summarise()”!).

- The “n()” function means that we just want to count the number of observations per group,

- And the observations will be found in the “Count” column. Note that you can replace “Count” by any name you want!

- And finally, we store this summary table into a new variable, which we call “data3”.

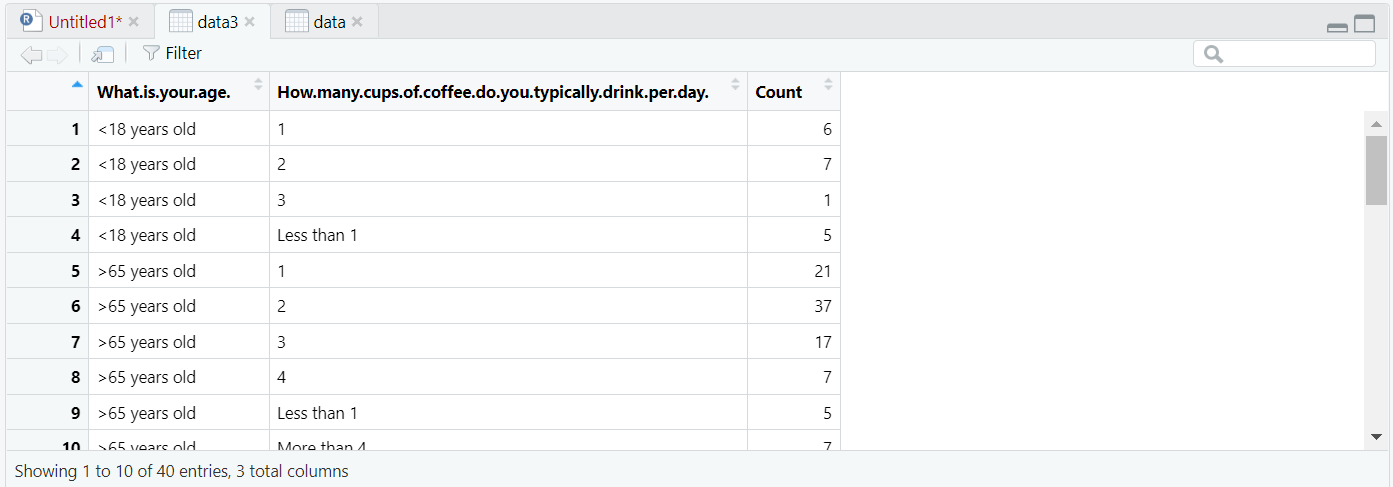

You should obtain something like this in the picture below:

There are of course many more ways to transform the data, summarize them, etc. This subsection was only a snapshot of what is possible to do with a very minimum number of lines of codes!

3.2.7 Plotting the data

Now that we have summarized data, we can plot to see what they look like. We will use a very straightforward function, called… “plot()”! Let’s see what it does with the codes below.

plot(x = data3$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day., y = data3$Count)

plot(x = data3$What.is.your.age., y = data3$Count)

We ran into a very superficial problem: R sorted the groups in alphabetical order, which is not quite straightforward! So we will need to reorder the levels before. Let’s do it with the code below:

data3$What.is.your.age. <- factor(data3$What.is.your.age., levels = c("<18 years old",

"18-24 years old",

"25-34 years old",

"35-44 years old",

"45-54 years old",

"55-64 years old",

">65 years old"))

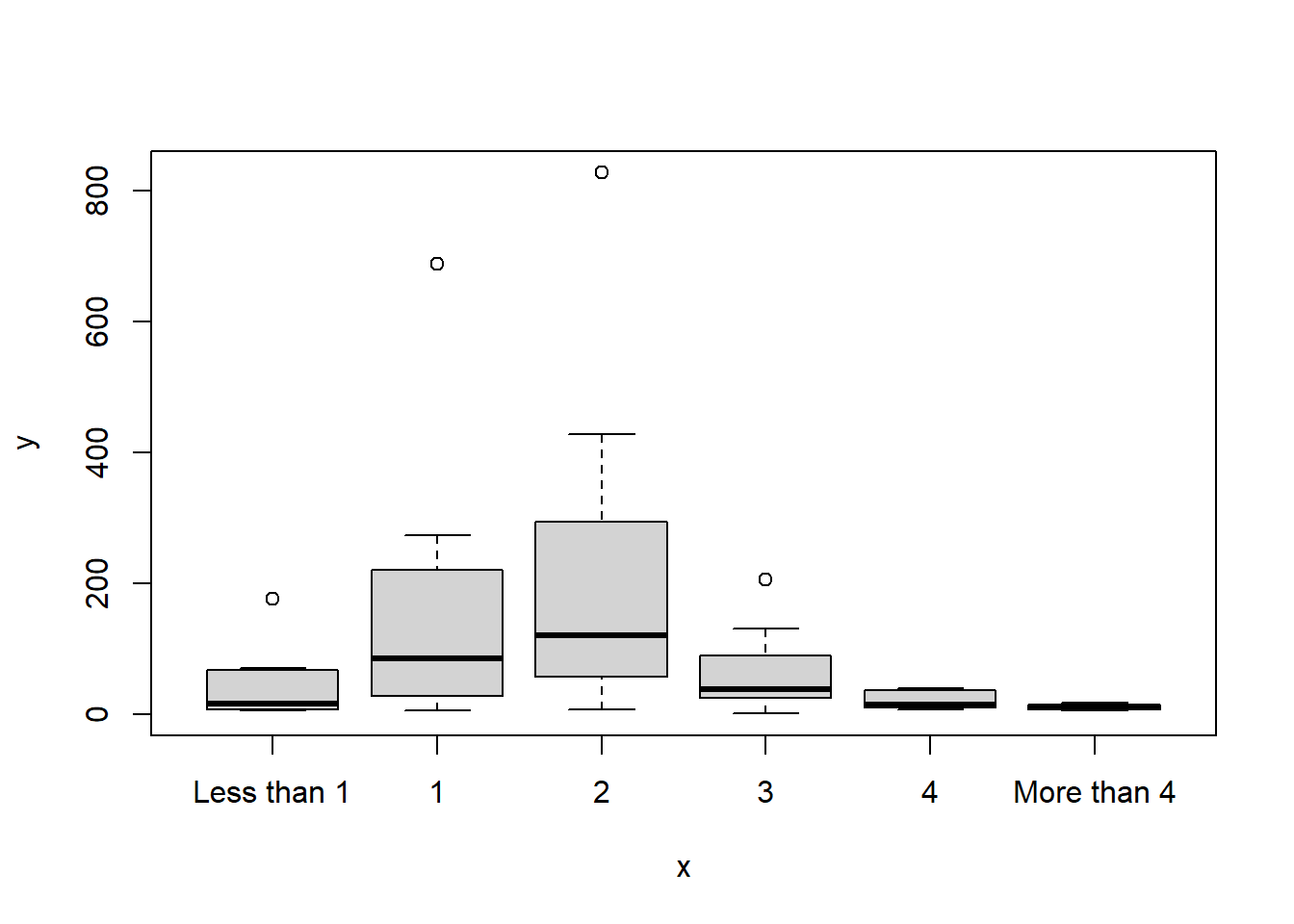

data3$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day. <- factor(data3$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day., levels = c("Less than 1",

"1",

"2",

"3",

"4",

"More than 4"))You can check whether this worked by using the “levels()” function we introduced above.

levels(data3$What.is.your.age.)[1] "<18 years old" "18-24 years old" "25-34 years old" "35-44 years old"

[5] "45-54 years old" "55-64 years old" ">65 years old" levels(data3$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day.)[1] "Less than 1" "1" "2" "3" "4"

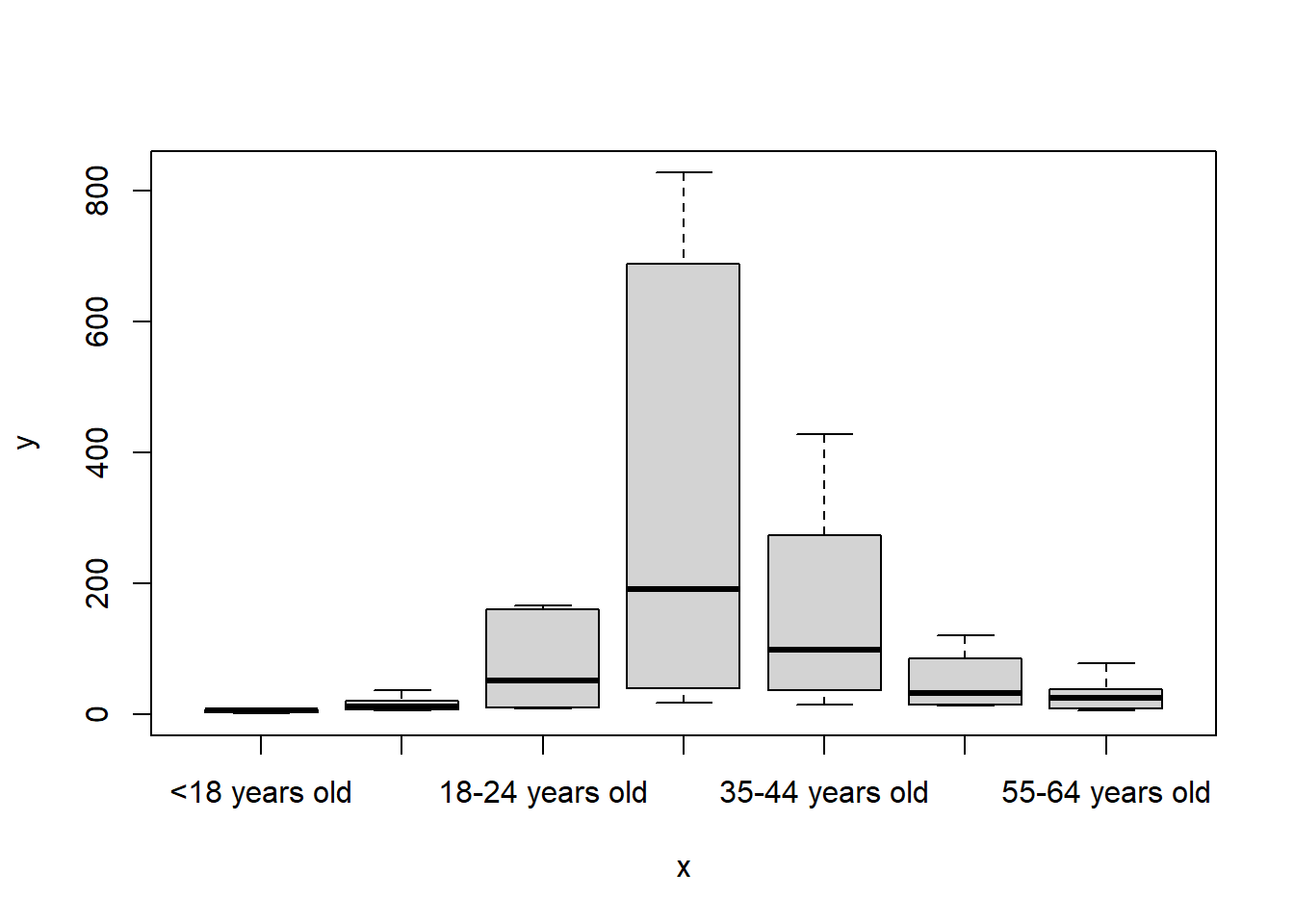

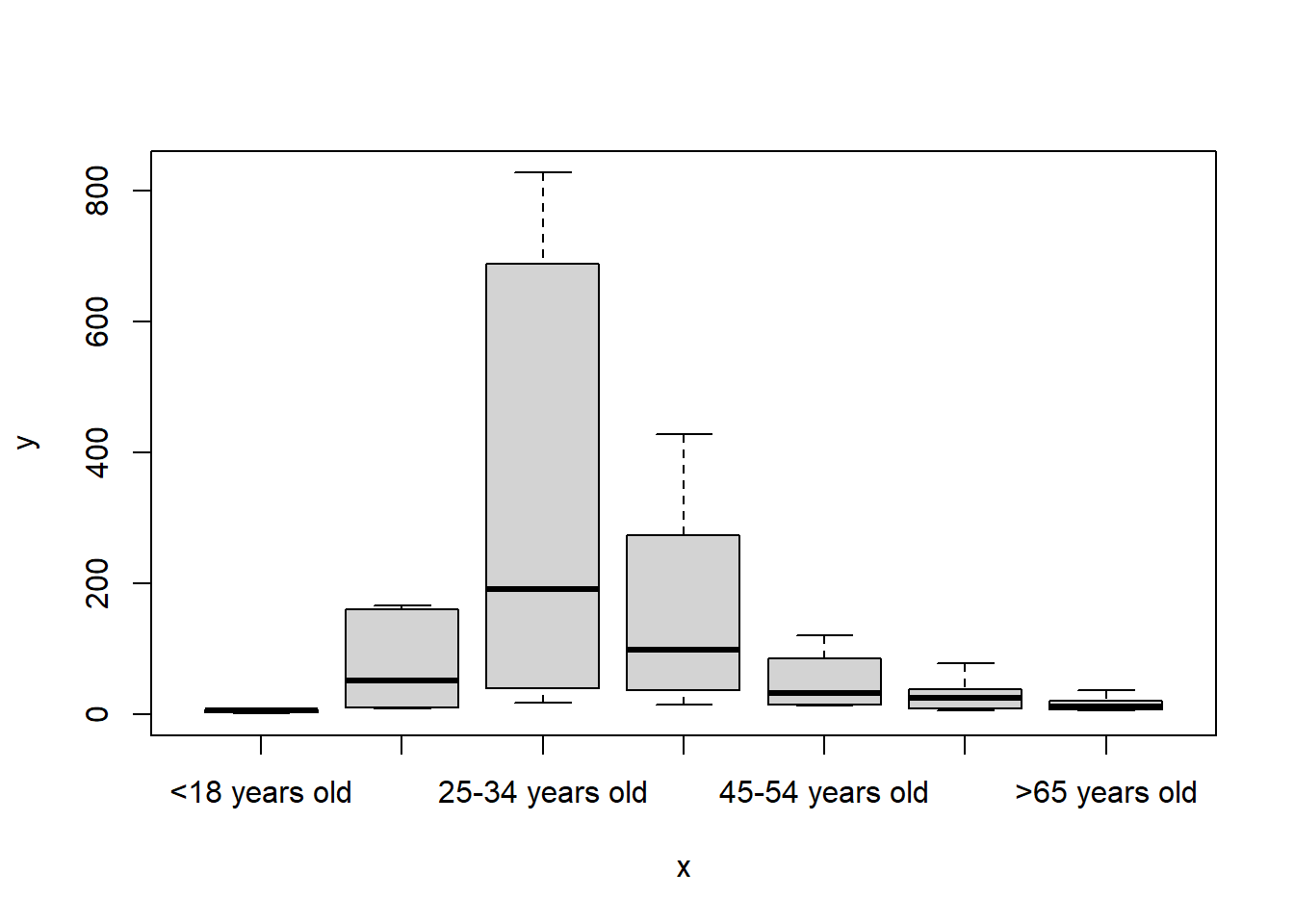

[6] "More than 4"Everything is in the order we want, now we can plot one more time, You will obtain the plots as below!

plot(x = data3$What.is.your.age., y = data3$Count)

plot(x = data3$How.many.cups.of.coffee.do.you.typically.drink.per.day., y = data3$Count)

The first plot shows that most of the participants are between 25 and 34 years old. The second plot indicates that most of the respondents drink between 1 and 2 cups of coffee everyday.

You might be curious whether there is an interaction, with older people drinking more coffee than younger people. In other words, you would need three variables in the codes… which is very difficult to do without other packages, espectially the “ggplot2” one! You can try by yourself!

3.2.8 Save data from R to your computer

For some reasons, we may want to save our data in the computer. But we are actually referring to two things at the same time:

Saving the R dataset, and

Exporting the R dataset such that we can open it with other programs.

Both are doable, and let’s start with the first option with the code below.

save(data3, file = "data3.Rdata")We just need the “save()” function, inside which we first tell R the dataset we want to save, and then the name of the file on the computer. We can choose the name of the file by ourself, as long as we do not forget the “.Rdata” extension. Once it is save, we can load the file later using the “load()” function.

load(file = "data3.Rdata")We may also want to save the data as a .csv file, readable by programs such as Excel. This is done with the code below:

write.csv(data3, "data3.csv", row.names = FALSE)Let’s unpack it:

- We use the “write.csv” function, and we provide details inside the parentheses for:

- The name of the dataset we want to export (here, data3),

- The name we want it to have in our computer (here, data3.csv), and

- the “row.names = FALSE” is here to say that we do not want the index of the rows. You can try and change to “TRUE” to see what happens.

It is also possible to export to .xlsx files, more directly readable by Excel, but this requires another library. We will encounter this in the rest of the tutorial.

3.2.9 R script of this section

You can find the R scripts including the codes presented in this section here. Don’t hesitate to use it and add comments for each line of code to make your own!

3.3 Common mistakes, or how to save a lot of time

You will run into many error messages, these intimidating red lines in the console block telling you that something wrong happened. We can spend hours trying to figure out what to do to make the codes work. Again, no worries! This is part of the learning process, and to be honest, even experts can’t avoid error messages. The most important thing is to learn from them, so that we are able to understand what the problem is, and how to solve it.

From my experience, there are mistakes we often make especially as first users of R. I remember that many students in the classes I attended and taught gave up on learning programming languages just because they had to spend too much time on debugging very basic mistakes, and they couldn’t focus on the opportunities R can offer. Below is a non-exhaustive list of such mistakes that I may update in the future.